When we say that somebody’s name is “mud” we mean that he or

she is completely out of favour for one reason or another. On the face of it,

that sounds like a perfectly reasonable word to use, given that mud is that

nasty, sticky or slippery stuff that we don’t like treading in if we can avoid

it.

However, the term has a much more interesting derivation,

concerning a tale of a miscarriage of justice and a name that just happened to

fit the use to which it was put.

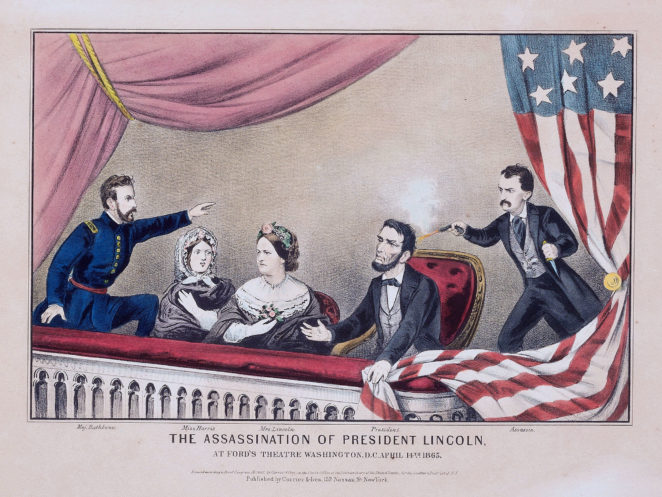

The story begins with the assassination of President Abraham

Lincoln in a box at Ford’s Theatre in Washington DC on 14th April

1865. His assassin, John Wilkes Booth, fired the fatal shot then jumped down on

to the stage of the theatre. This proved to be too great a height for safety,

because Booth broke his leg when he landed and it was only with some difficulty

that he was able to leave the theatre, mount his horse and escape.

Once safely outside Washington, Booth found a doctor to

treat his injury. This was Dr Samuel Mudd, who did what he was asked, after

which Booth rode away.

Dr Mudd only realized who his patient had been when news of

the assassination reached everyone the following day. He promptly informed the authorities

that he had seen and treated the assassin, but the response he got was far from

what he expected. Instead of being thanked for providing valuable information,

he was arrested and charged for apparently being a friend of Booth and part of

a conspiracy to kill the President.

Giving aid to the man who killed Abraham Lincoln was reckoned

by the general public, and the court that tried Dr Mudd, as being a heinous

crime that deserved a heavy punishment, and a sentence of life imprisonment was

what he got, despite his claim that he had no idea who Booth was at the time he

had treated his injury.

It was not until 1869 that Dr Mudd was pardoned and released

from jail, but there were still plenty of people who did not believe his

protestations of innocence. His name therefore continued to be “mud” for the

rest of his life, and “mud” has stuck to many other people in later years whose

reputation has been seriously tarnished.

© John Welford